Algorithm to fight cyberbullying

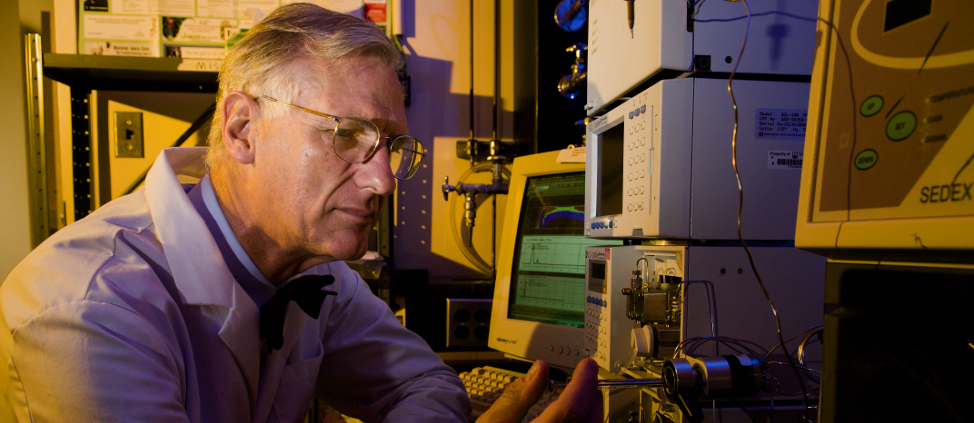

Blacksburg, Va., April 20 – Professor Bert Huang: Huang continues his research on algorithms to detect cyberbullying. His tool is only about halfway complete as he looks to take it to the next level of preventing cyberbullying. Photo: Johnny Kraft

by Johnny Kraft–

Cyberbullying is quickly developing into one of the most popular forms of bullying as social media and technology can be used as a weapon 24 hours a day, seven days a week. However, an assistant professor at Virginia Tech has built his own weapon in the battle against cyberbullying.

Professor Bert Huang has developed an algorithm to detect traces of cyberbullying. Huang is an assistant professor in the Virginia Tech Department of Computer Science, where he is using his knowledge of machine learning to develop algorithms to combat cyberbullying.

According to bullying statistics, about half of adolescents experience some form of cyberbullying, and 10 to 20 percent experience it regularly. However, Huang has found in his research that adults experience cyberbullying more frequently than people realize, and that men experience about the same amount of cyberbullying as women, although they are much different forms of cyberbullying.

Huang developed computer algorithms to identify cyberbullying automatically by using machine learning, which is a type of artificial intelligence that provides computers with the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed.

“We have to provide information as human experts for the machine-learning algorithm to learn from where these are explicit examples of here’s something that I am looking and here’s something that I’m not looking for,” said Huang. “So in this case, it would be here’s an example of cyberbullying and here’s an example of not cyberbullying. Doing that is really expensive and takes a lot of human effort, and is really tricky for humans to do.”

According to DoSomething.org, 81 percent of teens believe cyberbullying is easier to get away with than bullying in person. Right now, the algorithm can only detect traces of cyberbullying, but Huang’s challenge is to eventually find a way to prevent cyberbullying after detection. Huang acknowledged this as the biggest obstacle and focus of his research.

“That’s the goal. There’s a big open problem beyond the detection task. So once you detect it, what do you do?” said Huang.

The algorithm is still developing, as it is not completely accurate yet. Huang hopes to keep evolving his weapon, as a practical tool for social media and other Internet users in the future, but the next step is not completely clear.

“There’s a big question of what you do if you actually detect cyberbullying. This is a problem that we as humans have not solved,” said Huang. “How you intervene and how you fix that problem is not obvious, so getting a computer to do that is an even harder problem.”

Blacksburg, Va., Virginia Tech Assistant Professor Bert Huang built an algorithm to detect traces of cyberbullying. Photo: berthuang.com